| Home | National AAUP | News | Resources | About This Site | Contact Us | Other Links |

|

|

Back to Index of Chapter-Building Strategies Download this article as a Word document Article Contents

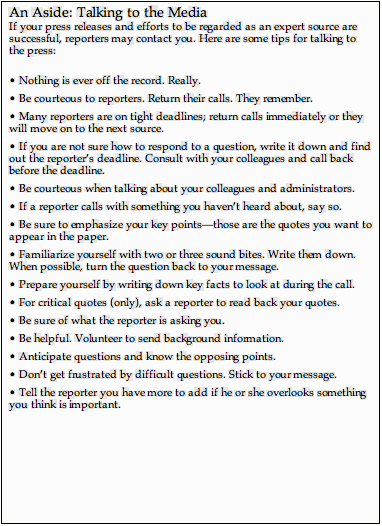

Communicating to Members and the Media by Newsletters, Web Sites, and Other MeansMedia CommunicationsThough members of the media may read your newsletters, newsletters are primarily for communicating with your membership or other faculty. An effective media relations program involves consistent outreach to members of the media in order to interest them in subjects that matter to faculty. Such outreach involves an effort to locate appropriate reporters, and it involves phone calls, e-mails, and other informal means of communication. This section covers two more formal types of communications pieces aimed at reporters—background packets and media releases—and two types aimed at a general audience through the media—op-eds and letters to the editor. Ultimately, the point of all media outreach is to persuade the larger audience that reads (or listens to or watches) the media. Background PacketsDevelop a packet of materials that includes basic information about your chapter or conference (contact information, programs, achievements), information about the AAUP and its policies, and clips of one or two recent news stories that quote an AAUP spokesperson. If your chapter or conference has been quoted, use those clips; otherwise, use clips featuring national AAUP spokespeople (making sure that the stories cast the AAUP in a favorable or neutral light!) As you develop a media outreach program, send this packet to each new reporter acquaintance, and as beats and assignments change, send it again to the new person on the higher education beat. The purpose is to inform them about the AAUP and to establish yourself as a reliable or expert source on certain topics, so they will call you or be receptive to your call when a related issue arises. You may also want to develop background packets about specific issues or on certain occasions. For example, if you are making a push for higher funding for core undergraduate programs at your institution, you might include information on what those courses consist of, what the funding trends have been in recent years, photocopies of research articles discussing the importance of core undergraduate programs, and other relevant materials, to send along with a media advisory. Releases and AdvisoriesA media (or press) release announces news; a media (or press) advisory lets reporters know of an upcoming event or news story, or provides deep background on an ongoing issue. When you have information that you really believe might interest multiple reporters, send out a release. If you have information that you think might interest one particular publication, you are better off calling to talk about it. Most publications receive many, many releases, many of which are completely unsuitable for the publication and go straight into the garbage. Sending out hundreds of press releases announcing your new chapter officers is a waste of time and money (though if you know of a few local media that might cover such a thing, by all means pursue those leads). You can send releases by mail, fax, or e-mail. Don’t forget your campus’ student newspaper, which may do much to influence the opinions of students, and perhaps of their parents. Form. Use your letterhead or a specially designed press release template for all releases, so they are recognizably yours. In the top left corner of a media release, put ”For Immediate Release,” followed by the date. If you want to delay publication of your news, write ”Embargoed until X date” instead. Do not break your own embargo. For a media advisory, put ”Media Advisory” followed by the date. In the top right corner, list names, e-mail addresses, and phone numbers of two contacts. Make sure these contacts can be easily reached (often a problem for academics who may be on the go). If your release is more than one page, write ”MORE” at the end of page 1 and list the contacts again, along with a short headline, in the upper-right hand corner of subsequent pages. Type “###” at the end of your release. Contents. If reporters aren’t interested in your headline, they won’t read the release. Make it punchy and use a large font. Place key information in the lead paragraph—who, why, when, where, and how. The most important information is in the lead, with additional paragraphs in descending order of importance. Generally, include quotes in the release; this makes it more interesting, and is a convenience for reporters, who may lift the quotes directly from your release. Avoid the passive voice. Use action verbs and make it lively. Avoid jargon and technical terms. Write simple, declarative sentences and short paragraphs. Your audience members are neither academics nor, necessarily, well versed in the details of higher education legislation, contract negotiations, or whatever your topic may be. Prepare boilerplate language describing the chapter and include it at the end of every release. Op-Eds and Letters to the EditorAn op-ed is an essay written by an outsider and published in the opinion section of a newspaper (as opposed to the unsigned editorials written by newspaper staff). Letters to the editor usually respond to particular articles that appeared in the paper, while op-eds generally do not. Both op-eds and letters to the editor should be kept relatively short and to the point. Newspapers will not publish a long, thorough treatise. They often edit submissions; by keeping yours short and to the point, you’ll reduce the chance that they will edit out the parts you thought were most important. A rule of thumb is to keep letters to around 200 words and op-eds to around 600, but you should also check the letters and op-ed sections and the Web site of the paper to which you’ll be submitting and see if it lists more specific guidelines. The Communications Consortium Media Center Web site at http://www.ccmc.org/oped.htm lists guidelines for many newspapers. Both op-eds and letters are typically about current or local events. If you see an opportunity to respond to an article in the paper, do so immediately. The newspaper world moves fast, and the editors will not be interested in publishing your response to an article that appeared a month ago. If you’re writing to your local paper, relate the issue to something local, if possible. The paper is more likely to accept an op-ed on contingent faculty that uses as a hook the fact that a number of jobs have just been cut on your campus or a new piece of legislation has just been signed in your state than one that analyzes the causes of the national trend over the past ten years. As you read the newspaper, keep an eye out for an opportunity to contribute to a debate or respond to something published. Look for a new angle or a fresh opinion on a topic of interest to the readership. Editors tend to avoid publishing obvious self-promotion such as essays talking about upcoming conferences or events. Keep the prose simple. Explain clearly in your first sentence why you are writing. Use vocabulary that the paper’s readers and editors will easily understand. Use paragraphs. Be polite. Don’t denounce the paper or rant. Be as positive as possible—your purpose is to persuade people, not insult them. The smaller and more local the paper, the greater the chance that it will accept your op-ed. Nationally read papers like the New York Times receive hundreds of submissions. Depending on your cause, you might get more mileage out of a couple of letters or op-eds in the campus or local paper than one in a national paper anyway. Consider whom you are trying to influence. Editors may pay more attention to your submission if it is signed by someone with relatively high status. When writing on matters of mutual interest (higher funding for higher education, for example), you might consider drafting an op-ed and asking the president of your institution to co-sign it. For an op-ed, write a cover letter briefly explaining your subject, why it is relevant, and a little about yourself, especially things that make you seem knowledgeable and/or locally entrenched (I am a professor of economics at Woolly Mammoth College and a twenty-year resident of this town). Make sure you include your name, address, day and evening phone numbers, and e-mail address. The editors will contact you to confirm that you wrote the op-ed or letter before publishing it and may give up if they cannot easily reach you. Even if your submission is not published, it demonstrates to the editors that there is an interest in stories on this issue, and that knowledgeable readers are watching the stories for inaccuracies and biases.

|

|